Abstract

This project models the black hole Sagittarius A*, with a primary focus on how light rays are realistically affected by the gravitational pull of a black hole, a key aspect of Einstein's theory of general relativity. Through the use of raymarching, our model incorporates gravity on each ray to model the black hole's Schwarzschild radius, as well as demonstrating how light from the surrounding space gets warped and distorted as photons approach the black hole. Overall, our project helps visualize interactions surrounding black holes that traditional ray tracing algorithms would struggle to accurately represent.

Technical Approach

Physical Equations

Coming to our technical approach, we explored ways to implement the effect of gravity on light. Initially, we considered modeling light trajectories using geodesic equations from general relativity. This would require us solving the geodesic differential equation: $$\frac{d^2 x^\mu}{d \lambda^2} + \Gamma^\mu_{\alpha \beta} \frac{d x^\alpha}{d \lambda} \frac{d x^\beta}{d \lambda} = 0$$ This approach was very computationally intensive and complex to implement within our project deadline. In adjusting to this problem, we decided that instead of gravity from a relativistic point of view and calculating geodesic paths, we can take a Newtonian approach that applied a gravitational force to the light rays.

First, we considered the Paczyński-Wiita pseudo-Newtonian potential according to the source “Thick accretion disks and supercritical luminosities” by Paczyński, B., & Wiita, P. J which closely imitates general relativity by diverging the Schwarzschild radius. However, there were still challenges like numerical integration stability issues when approaching the Schwarzschild radius (rs). We also learned the difficulty of fitting it into our existing GPU-based integration loop. Therefore, we were not able to fully integrate it into our simulation pipeline.

Finally, we decided to instead use a much simpler Newtonian force law (1/r^2) where r is the distance between the black hole and the light (photon). This Newtonian force law is almost identical to the Paczyński-Wiita pseudo-Newtonian potential. According to the source Spacetime and Geometry by Carroll, it comes from the fact that F(r) = GM/r^2. Therefore, at each timestep, we measured the ray's distance from the black hole center. And, we compute a gravitational acceleration vector toward the black hole, adjust the ray's direction by adding this acceleration and finally, renormalizing the direction and position. This allowed us to bend the light paths in a physically intuitive way while we were able to keep the math and performance manageable. We learned that the Newtonian (1/r^2) approach is simple, computationally light and stable, but it allows light to get unrealistically close to the black hole without sufficient bending.

General Ray Marching

Our project uses OpenGL with raymarching and a complex fragment shader to render all the visuals seen. We start by creating a quad that consumes the entire window, and then we use the fragment shader to cast rays out from the camera into the scene.

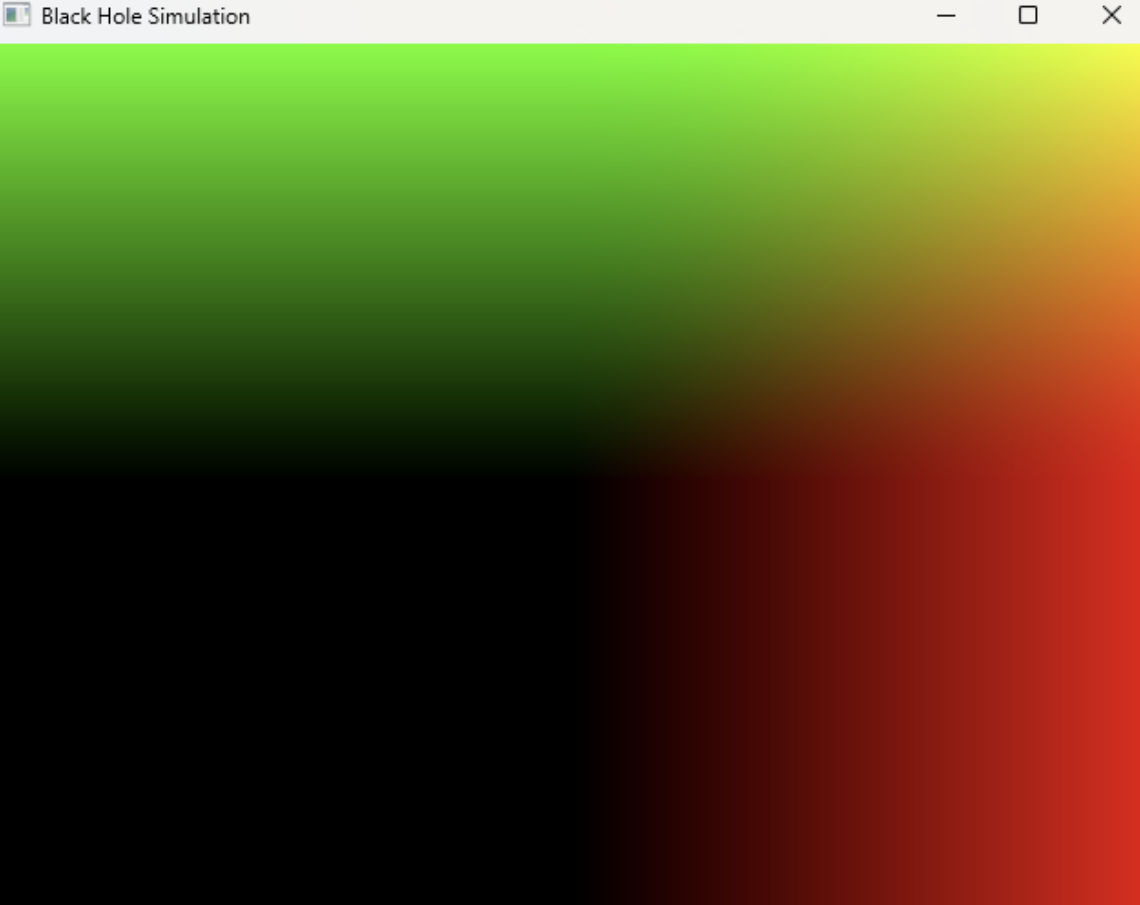

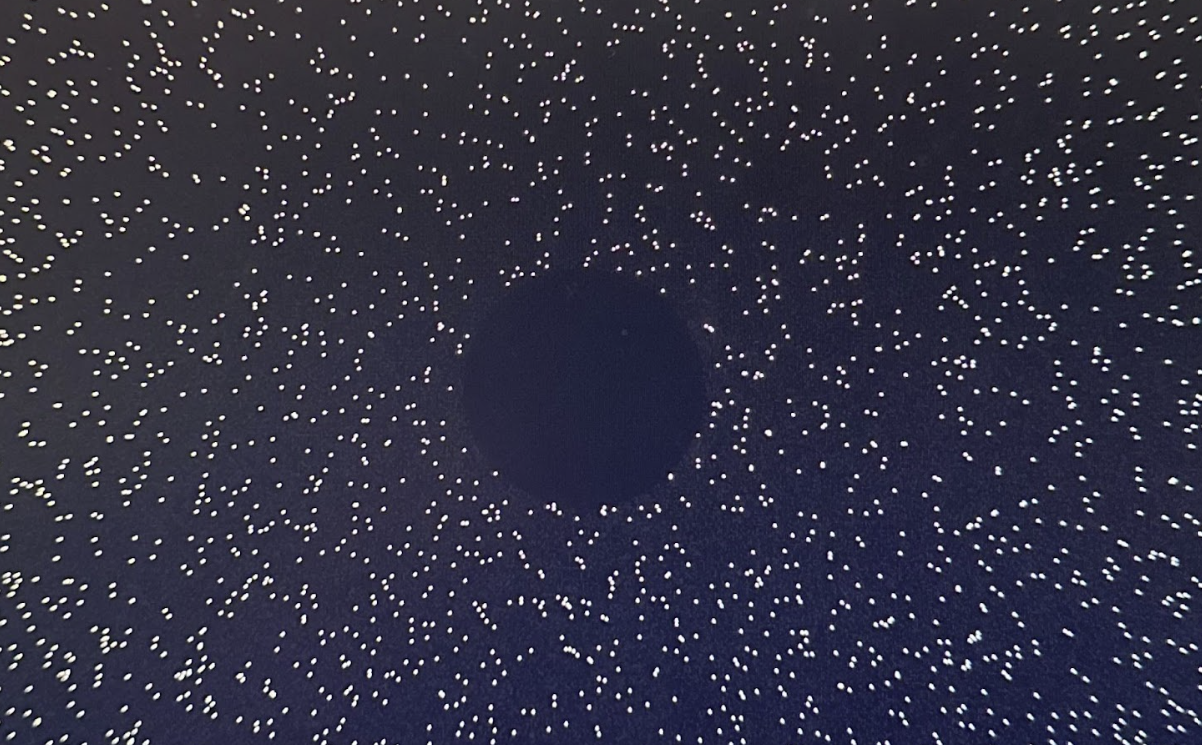

This image shows the UV coordinates of each pixel on the screen and represents the angles that the rays will be sent out:

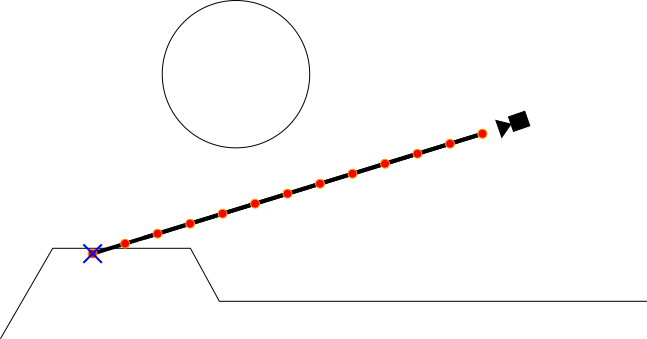

It is important to note that our model uses fixed-distance raymarching, meaning our rays travel at set intervals before checking their distance to objects in the scene, as seen in the image below.

Once these rays are sent out, we can use a signed distance function for a sphere to represent the distance from the ray's current position to the black hole. To do this, we use the formula:

float signedDistanceSphere(vec3 p, vec3 center, float r){

return length(p - center) - r;

}

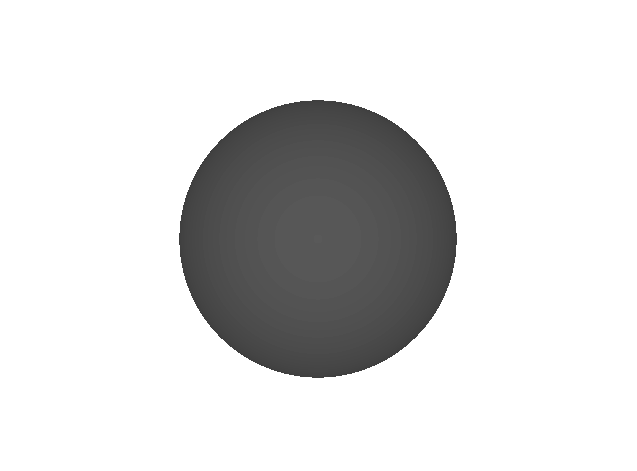

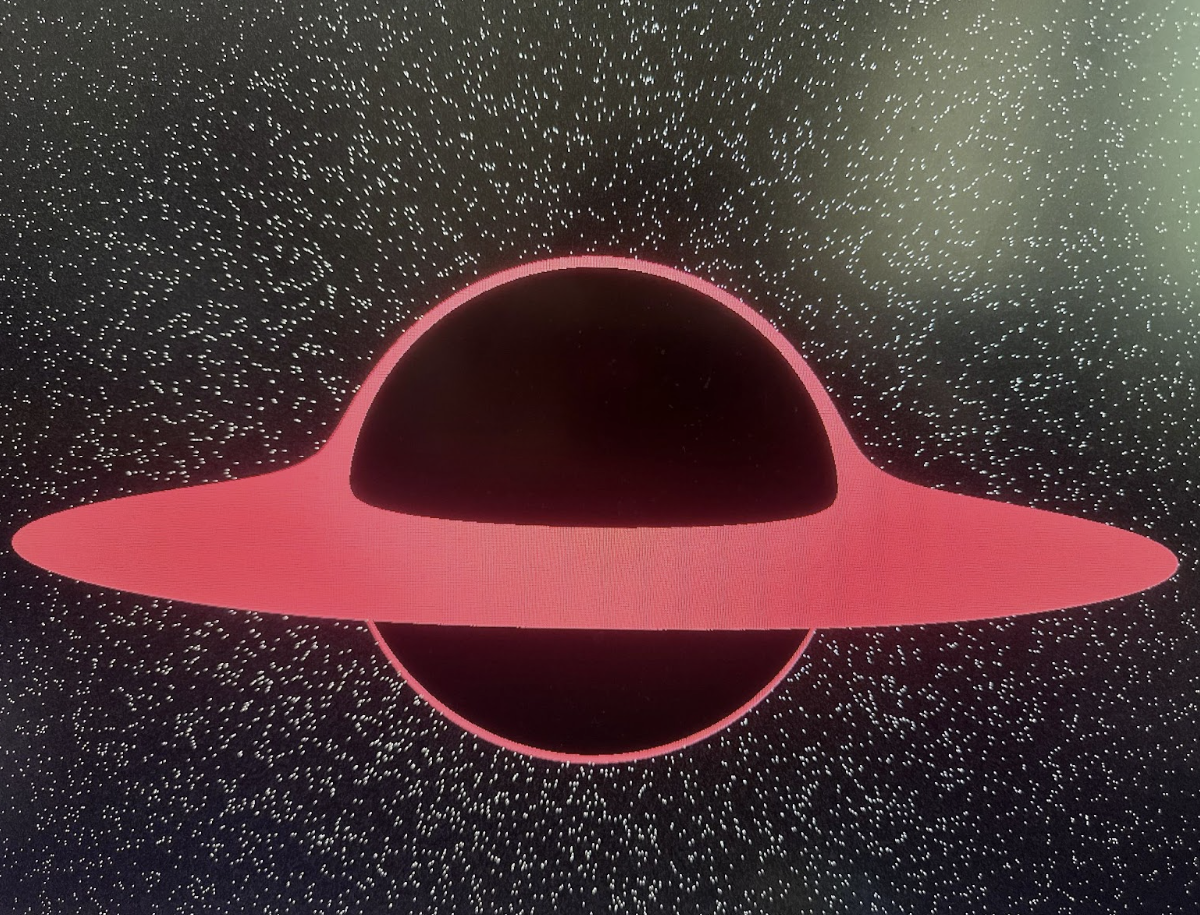

During the early development of our engine, this just returned a sphere that was shaded based on the distance that the ray travelled. Even just this simple technique yielded satisfying 3d renders:

When the value of the signed distance function is <= 0.001 or some small number, we can confidently say that the ray has hit the event horizon of the black hole, and thus we will terminate the ray. In our fragment shader, this means the color of the pixel will return:

color += vec3(0,0,0); //color includes all previous radiance the ray has collected

return;

This simple technique, coupled with our gravity system and background, slowly gained the ability to create more and more complicated renders.

|

|

|

|

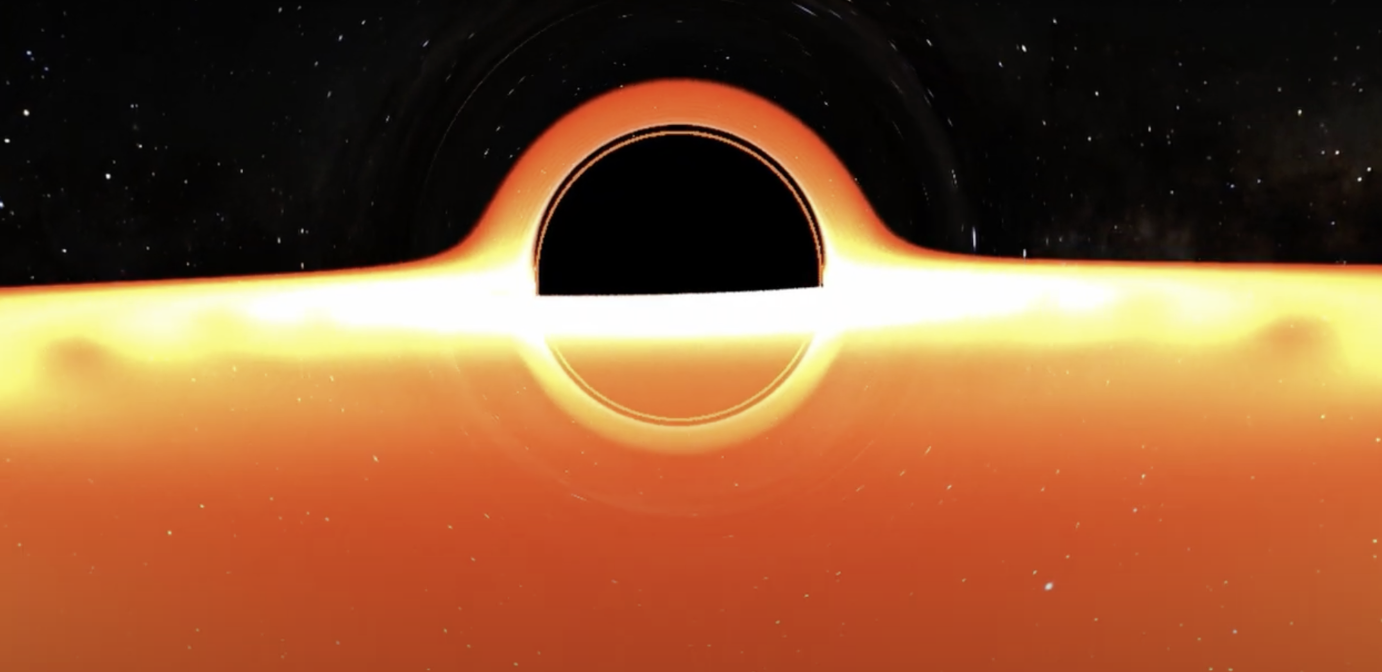

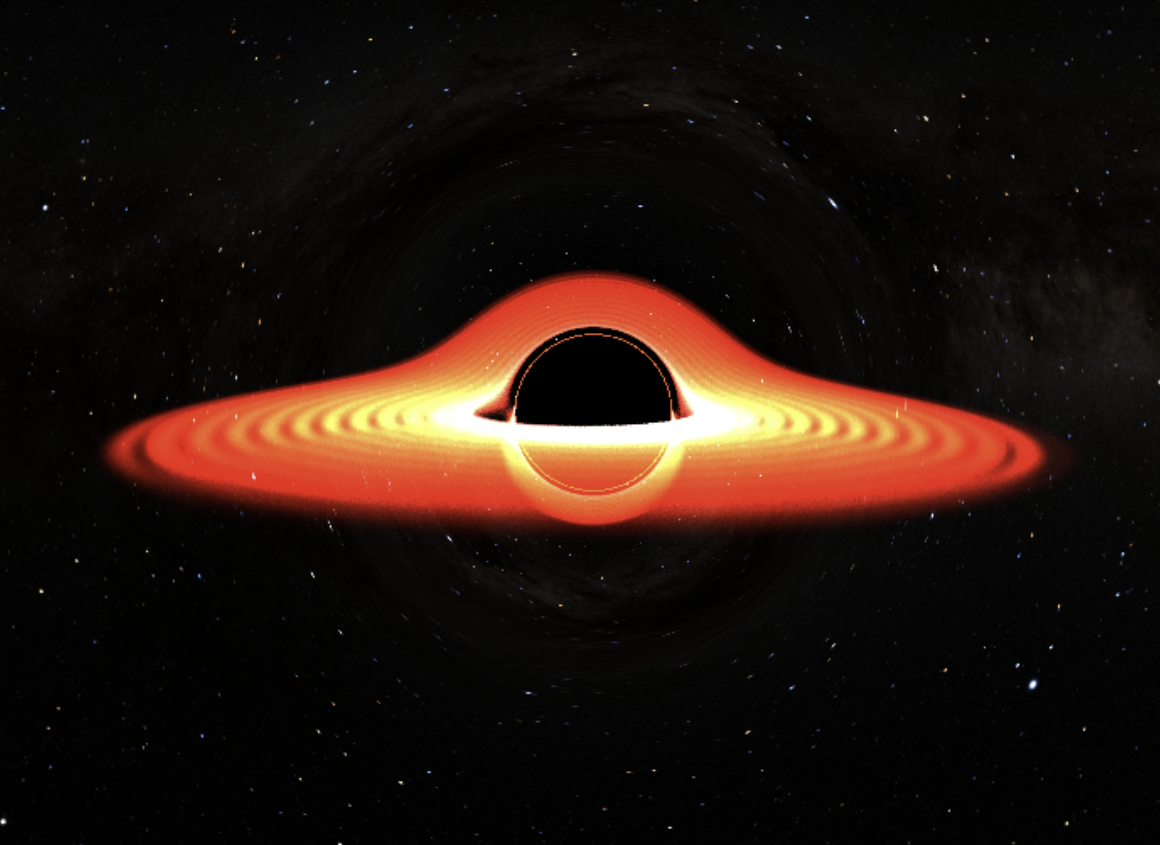

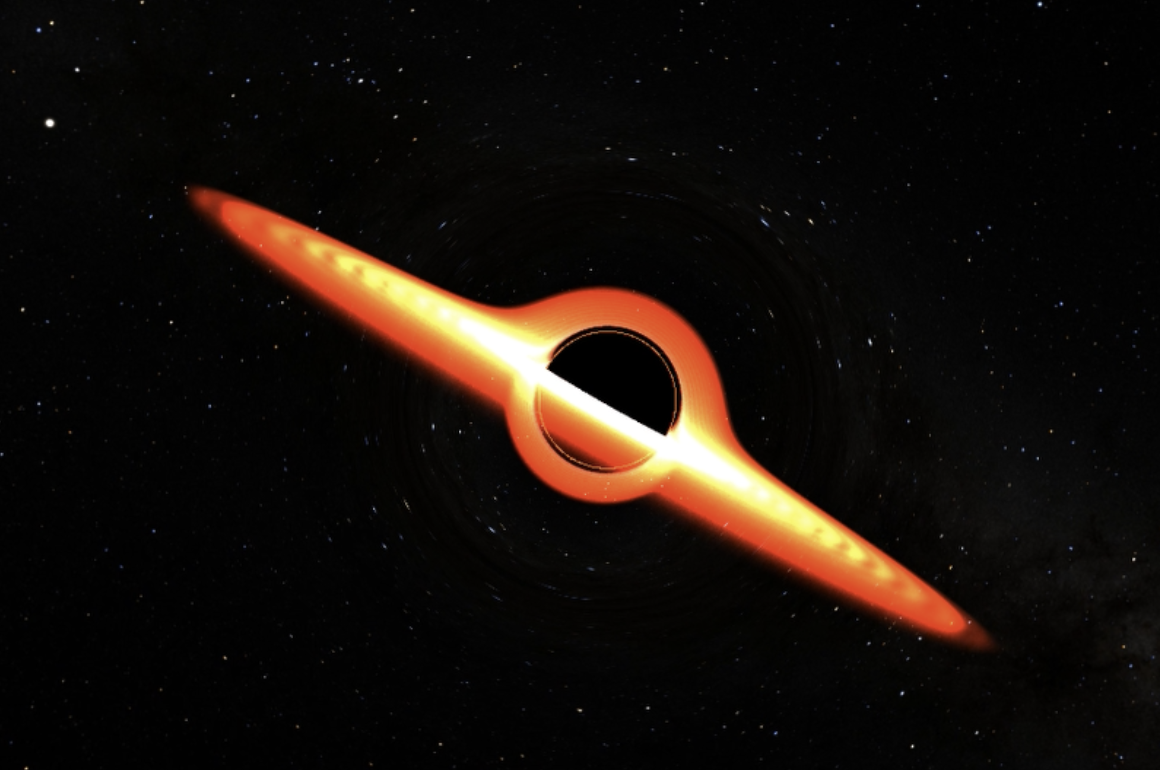

Accretion Disk

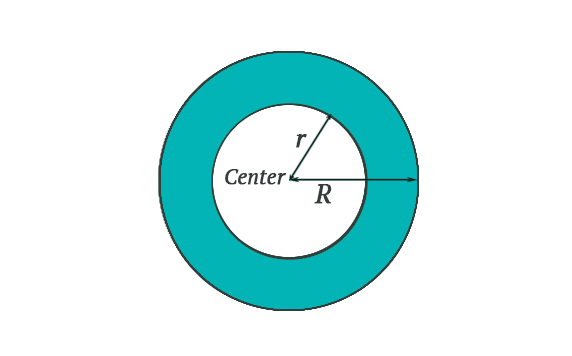

The accretion disk is mainly modelled after an 'annulus' shape, which looks follows the shape of a flat torus:

In the case of a Schwarzschild black hole, the inner radius of the accretion disk is: $$3 R_s$$ where \( R_s \) is the Schwarzschild radius, also known as the event horizon. By placing the 2D annulus shape into the xz-plane, we test whether the ray intersects the annulus every time it crosses the xz-plane (i.e., when the \( y \) coordinate changes sign from positive to negative or vice versa). Checking for intersection with the disk is straightforward: we use 2D distance functions to determine if the ray's \( x \) and \( z \) coordinates lie between the inner and outer radii of the annulus.

Although this is not a physically accurate model of why the accretion disk glows, we visually replicate this phenomenon—including the photon ring—by assigning a color value to the disk and adding that to the total color of the ray. Additionally, we introduce circular noise along the xy-plane using the function: $$\sin\left(\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\right) = 0$$

Gravitational Lensing / HDR Background

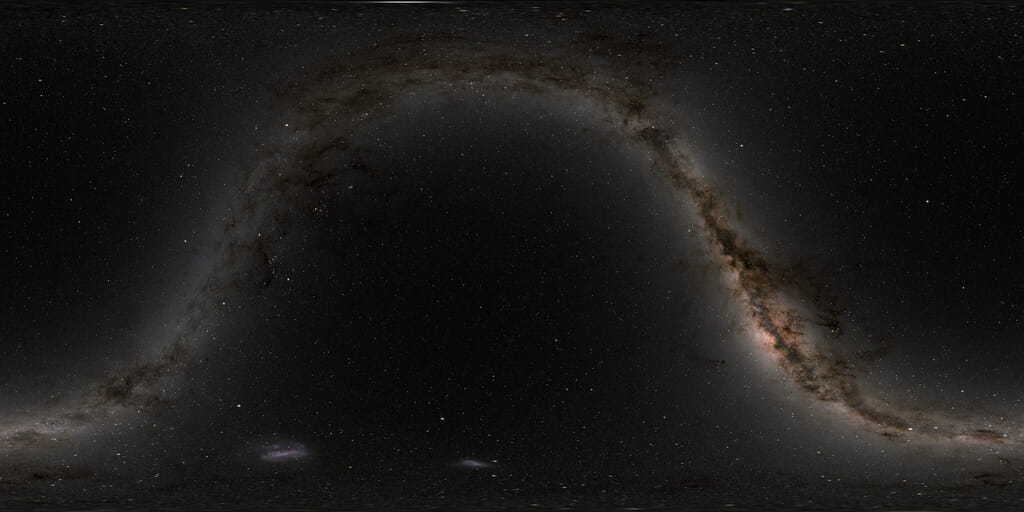

To create the gravitational lensing effect, we tracked each ray sent out from the camera that missed both the black hole and the accretion disk. Once past, the rays' direction were used to determine at what point on a spherical area around the black hole does the ray eventually hit via the angle the ray made with the positive y-axis (theta Θ) and the angle made with the positive x-axis (phi 𝜙).

This spherical area is represented through an HDR background from NASA, which is a starmap that depicts the starfield surrounding the real Sagittarius A*. This background is then given a uv coordinate system through the use of stb_image header and OpenGL's texture mapping, allowing us to fill in the empty space around the black hole. Using theta and phi, the uv coordinate on the HDR background is calculated and then used to sample the corresponding texel, which is sent to our fragment shader to be displayed. Since the gravitational forces already influenced the rays' directions, the resulting textures naturally mimic the warping effect, even revealing parts of the background that appear to come from behind the black hole.

Camera movement/control

To provide an interactive experience, we process user inputs and allow them to fly around in space, get closer to the black hole, and observe the space around them. Our program listens for inputs from the WASD, left shift, and space keys to manipulate the camera's xyz coordinates, as well as changes in the mouse position to change the direction the camera is facing. We modeled the camera similarly to how it was parametrized in lecture; we gave it an origin, up/forward vectors, and some other vectors for completeness, like manually calculating the right vector and saving that. With these parameters, we could translate rays from being defined in world space to being in terms of camera space. This allows for us to keep the same processing/logic for the rest of our program, but enables our display to change based on the camera's position and view directions.

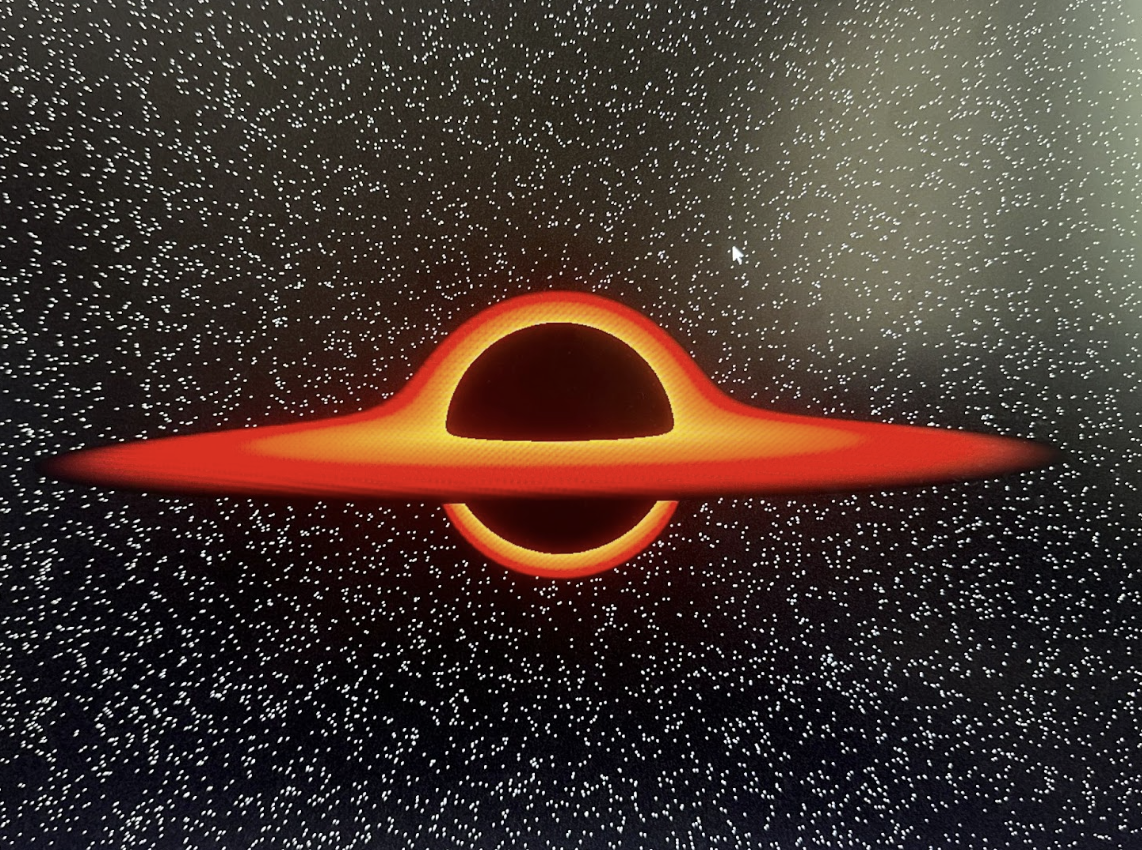

Results

|

|

Conclusions

Overall, the physics turned out to be a lot more complicated than we imagined, but we were still able to get great results using simplier equations. Additionally, the ray marching plus fragment shader combination provided a lot more flexibility compared to ray tracing, yet still requires analytical definitions and signed distance functions. Despite the added challenges, it proved to be worthwhile as it made our simulation visually and accurately possible. Finally, one of our biggest lessons that we learned as that OpenGL projects, and C++ projects in general, are difficult to set up. They require a lot more knowledge on frameworks and tools such as cmake than we expected, yet once we got them set up, they provided a lot of the necessary structure to our project.

Contributions

- Jake Pastoria

- Project Setup, Raymarching Algorithm, Newtonian Gravity, Accretion Disk, Photon Ring, Video

- Ryan Trinh

- HDR background, Gravitational Lensing, Website

- Phone Min

- Research on Paczyński-Wiita acceleration, 4th-Order RK Geodesic Equation

- Ryan Lee

- Mac Support and Set Up, Input Processing, Camera Transforms